The Port Neighborhood Grant, Cambridge, MA

LCC Grant from Arlington Cultural Council

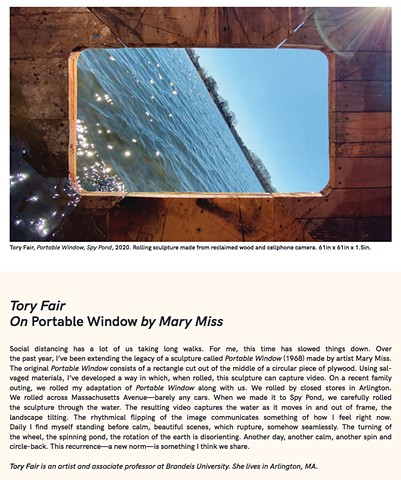

ICA at MECA Portable Window

Boston Art Review

Residency at RAIR Philly

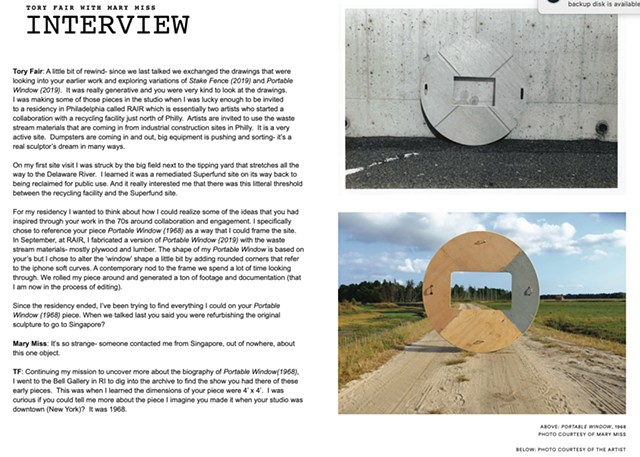

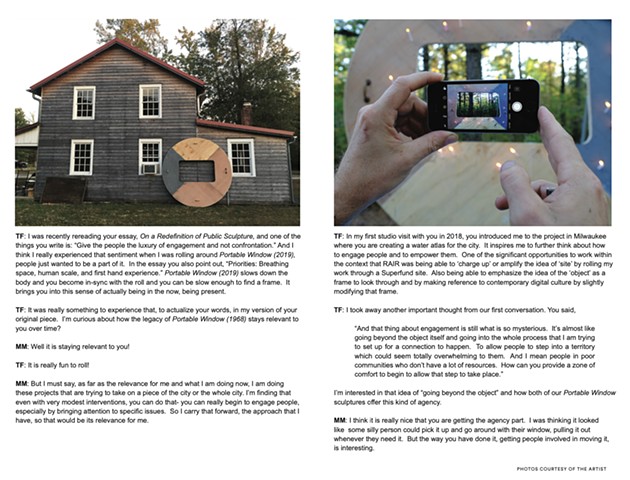

Excerpt from interview with Mary Miss, RAIR catalogue 2020.

Residency at RAIR Philly

Excerpt from interview with Mary Miss, RAIR catalogue 2020.

Review in the Boston Globe

Essay by Susan Stoops on Heap in South Boston, Proof Gallery

Tory Fair: Heap

“…basically, you make things out of the structure of who you are.” Jackie Winsor, 19791

Tory Fair’s heap of cast objects whose foam, concrete, and rubber physicalities bear the memories of absent originals – a favorite mug, her work boots, a camera that once belonged to her grandmother, a well-used soccer ball, a woven basket from time living in the Southwest – is the sole structure occupying the main room of Proof Gallery in South Boston. Its dimensions and orientation are in direct response to the narrow space, and invite immediate investigation upon entering the room. What does one recognize? What sensations are stirred? What meaning resides in the dialectic Fair creates between this mass of material and the evocative realm of interpretation?

Close exploration of this gritty mound also reveals forms cast from the natural environment, including the occasional blooms of lilies. But most numerous are crystalline shapes in a dramatic range of sizes and postures, and often sprouting from or slicing through the domestic memorabilia. It is a disorienting experience of the familiar, muted by blackened and ashen surfaces. Moments of dappled light subtly animate the entire expanse, providing an episode of the ephemeral amidst the emotional and physical weight of extreme accumulation.

Things in the world once distinguished by their unique function, materiality, color, or scent have been translated into sculptural abstractions. Their physical natures are now rendered primarily in terms of volume and scale and, like the rocks of a stone wall – individual yet interdependent – they perform particular formal tasks in relation to one another. Each element of Heap, whether visible in part or in its entirety, is comprehended as complete and utterly necessary. As one visually digs through this sculptural treasure trove, one not only discovers Fair’s repertoire of cast objects but also her talent for creating inexplicable yet memorable juxtapositions.2

Fair recalled that when she embarked on Heap she approached it very, “pragmatically… I was open to the process and depending on it to lead me somewhere new. I was conscious that I wanted to generate a long-term endeavor with some ambition, so I began working with smaller pieces that I could accumulate into something larger. I was committing to a few stubborn ideas in order to turn a page for me in my studio.”

The aesthetic character of Fair’s heap – its decidedly low-tech, crude nature which she finds “futile and hopeful” – can be traced to her hands-on process of making molds. She trusts the imperfections, blemishes, and fissures that occur to become the distinguishing surface aspects of multiple casts of the same object. “All the objects are rough and rugged and I love the feeling that they might have been dug up from the ground and discovered like a fossil, as though they themselves were made from compression and torque and foul bite. Although multiples each comes out differently – different make ups, different mold lines, different weights and tones. Maybe I wanted them to feel a little out of my control – sort of a way to mimic nature and use the crystal as a mentor.”

Even Fair’s approach to creating an element of light in Heap was decidedly sculptural and not engaged with new technology. Turning to her archive of slides of her earlier work (a poetic addition to Heap’s dialectic of memories of absent originals), Fair cut specifically shaped holes in the slide film and then inserted the repurposed slides into several old slide projectors mounted above the installation. In a room without any natural light, these spots of projected light, while accentuating details of certain objects, conceptually extend the spatial reach of Heap, linking it to surrounds beyond the gallery walls.

Fair’s aesthetic of connectedness builds upon the phenomenological reading of sculpture proposed decades earlier by Rosalind Krauss as an identification of the self “in contact with the space of the world.”3 In 1991, after graduating from Harvard with a degree in sculpture and religion, Fair was awarded a Gardner Travelling Fellowship that supported a year of driving across the country and studying Native American mounds, sun daggers, and medicine wheels. The year also marked a significant life experience that would encourage a convergence of her interests in sculpture, agnosticism, architecture, and the landscape – Fair sought out James Turrell in Flagstaff and assisted on his Roden Crater Project for the next three years.

“My hunch at the time, to go find the Roden Crater was rooted in my love of how Turrell grounds his work in moments of the everyday such as the rising of the sun and the setting of the moon, the basics. I love how he takes these earthly moments that are very accessible and moments that are taken for granted and heightens them in order to take pause and really participate with them.”

Since then, Fair’s sculpture, in all its varieties of form, has been conceived as a dialogue with her environs – sports-inspired floor installations rooted in her childhood backyard and her years as a soccer player; objects and bodies sprouting flowers reminiscent of those populating her mother’s gardens at their 18th-century New Jersey farmhouse; body casts of herself in physical contact with the environs whether gallery walls and floor or an outdoor terrace; and casts of domestic objects in our midst which trigger routine interactions such as reading a book, gazing into a mirror, or watching TV.4

Heap marks both a significant move forward for Fair’s work and a reflection on her past: “…this installation is a very concise (not a word I would expect to use) way to participate in my own yearning for a connection to my surroundings, particularly the landscape where I grew up (Green Village, New Jersey) and the landscape I sought out after college (Flagstaff, Arizona). The overall gesture of accumulating objects to make a mark is both physical and sentimental. Because these are my sculptures that are accumulating in Heap, I feel a sense of release and a strange sense of empathy: here is my work, let me give it back to the surface of the earth.”

It is worth noting the kinship between Fair’s accumulation and the sculptural explorations of Robert Smithson (1938-1973), which often took the form of piles (amorphous and contained) of soil, minerals, or rocks in dialogue with a distant site. Smithson imagined sculpture as a form of temporal space capable of engaging “remote pasts and futures” as well as bridging the conceptual divide between the natural world and the built environment. During the past few years the crystal, a common yet exquisite form of natural order and repeating pattern that also preoccupied Smithson, has become central to Fair’s sculptural practice. Initially embellishing other objects and surfaces to signify a transformation of the mundane (such as Windshield, 2013), the crystal form (based on six-sided prisms each terminating in a six-sided pyramid) is now the dominant structural component to which other objects in Heap have adapted.

“Why toe the line with the perfection of a crystal? Probably a bad idea, but one I wanted to grapple with. The earth is making these things, why don’t I borrow the form, capture it in molds, and bring it into my immediate surround. When I started fusing them with pillows and soccer balls and waffles, I approached the crystal as some sort of compass point. How can I fortify this frozen waffle that my kid is eating for breakfast? I focused my objects on circular forms – baskets, frames, coasters – in order that the crystals seemed to suggest a cardinal point. The mundane objects seem to almost welcome the crystals like adding a lost limb of sorts. I expanded my objects to include other forms including boots, cameras, and flowers. Now I can imagine crystals growing out of everything! Like some sort of wild vortex reclamation of the landscape!”

Rather than a proliferation of perfection, the mash-up of crystals populating Heap is subject to Fair’s willful experimentation and imagination. Although all were cast from a small quartz specimen, they reappear as opaque solids in an unpredictable array of sizes, positions, and textures (from finger- to arm-length, from erect to collapsed, from smooth rubber to encrusted concrete), while generating as many allusions (from the architectural to the anthropomorphic, including most obviously, the phallic). Perhaps as a foil to Heap’s apparent precariousness, Fair constructed passages of geometry (albeit often battered and bruised) creating an inherent logic between abutting forms: repeating circular shapes (pillow, soccer ball, frozen waffle, and basket); a waffle’s imperfect but legible grid; the pyramidal tips of crystals; the soccer ball’s pentagon-and-hexagon pattern. Fair’s subjectivized embrace of repetition and the paradoxical freedoms it allows also becomes an eloquent metaphor for finding meaning and moments of clarity in the daily routines of our lives, lives populated by objects like those she chose to cast.

That Fair has been committed to casting multiples in the service of reclaiming an object’s individuality reveals something about her character – an uncommon combination of fortitude and humility. Maturing artistically amidst a prevalence of contemporary sculptures and immersive installations which repurpose found objects and materials – from the innovations of Judy Pfaff to the work of Sarah Sze – Fair has dedicated her studio practice to the translation of objects into other objects. Fair’s work has affinities with Amanda Ross-Ho’s oversize jewelry and jersey constructions and Alice Channer’s casts of flat fabric into curved resin and aluminum sculptures and she shares with those peers a keen awareness of objects’ material properties and how they tap into our collective cultural and physical associations. Heap not only connects us to the complex world around us but also invites introspection and activates in each of us a fundamental capacity in which interpretation and imagination thrive.

“…the crystals and objects in the work help me feel I am operating with contradictions in an overall affirming gesture. Sculpture is an affirmation. It participates in the literal world. Futility? False mysticism? Fortifying the ethereal? All things I see the rigor of sculpture doing very well. Sculpture has a way of using its physicality to address things that are not physical at all.”

Susan L. Stoops

Independent Curator of Contemporary Art

NotesAll quotes by the artist are from conversations and correspondence with the author during August – October, 2015.

1. Jackie Winsor, quoted in John Gruen, “Jackie Winsor: Eloquence of a ‘Yankee Pioneer’,” ARTnews (March 1979), 57.

2. During the process of making the sculptures for Heap, Fair made a series of photos of several isolated objects, which can be understood individually as “portraits” of the sculptures and collectively as a graphic index of the objects in the installation.

3. Rosalind Krauss, “Sense and Sensibility: Reflections on Post ‘60s Sculpture,” Artforum (November 1973), 43-53.

4. For two excellent overviews of Fair’s work, see Francine Koslow Miller, “The Metamorphosis of Tory Fair,” Sculpture Magazine (October, 2010), 43-47; and Dina Deitsch, Tory Fair: Testing a World View (Again), exhibition brochure (Lincoln, Massachusetts: DeCordova Sculpture Park and Museum, 2011).